Introduction

SBA-15 is a highly ordered mesoporous silica material with a two-dimensional hexagonal structure, large surface area, and tunable pore size. Since its discovery by Zhao et al. in 1998 [1,2], SBA-15 has attracted significant attention for applications in catalysis, adsorption, drug delivery, and other fields. This comprehensive review focuses on strategies to optimize the synthesis of SBA-15 from tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) to achieve the highest surface area while maintaining good structural properties and stability. We will also explore the fundamental aspects of SBA-15 formation, characterization techniques, and potential applications.

Historical Context and Development

The development of SBA-15 was a significant milestone in the field of mesoporous materials. It followed the discovery of the M41S family of mesoporous molecular sieves, including MCM-41, by researchers at Mobil Oil Corporation in 1992 [13]. While MCM-41 materials were groundbreaking, they suffered from relatively thin pore walls and limited hydrothermal stability.

SBA-15, developed at the University of California, Santa Barbara, addressed these limitations by utilizing a non-ionic triblock copolymer (Pluronic P123) as the structure-directing agent under acidic conditions. This approach resulted in materials with larger pores, thicker pore walls, and improved hydrothermal stability compared to MCM-41 [1,2].

Fundamental Aspects of SBA-15

Structure and Properties

SBA-15 is characterized by a highly ordered 2D hexagonal array of cylindrical mesopores with a uniform pore size distribution. Key structural features include:

- Pore diameter: Typically 5-30 nm (tunable)

- Wall thickness: 3-6 nm (generally thicker than MCM-41)

- Surface area: 600-1000 m²/g

- Pore volume: Up to 2.5 cm³/g

- Microporosity: Present within the pore walls, contributing to connectivity

The thick pore walls and the presence of micropores contribute to the material’s high thermal and hydrothermal stability as presented in Figure 1 [3,9].

Figure 1 TEM images of samples before and after hydrothermal treatment: (A) sample S-1; (B) sample S-1 after the steam treatment of 3 h at 600 °C; (C) sample S-1 after the steam treatment at 800 °C for 3 h; (D) sample S-6; (E) sample S-6 after the steam treatment of 3 h at 800 °C; (F) sample S-7 after the steam treatment of 3 h at 800 °C. [9]

Synthesis Mechanism

Understanding the formation mechanism of SBA-15 is crucial for optimizing its synthesis. The process involves several key stages:

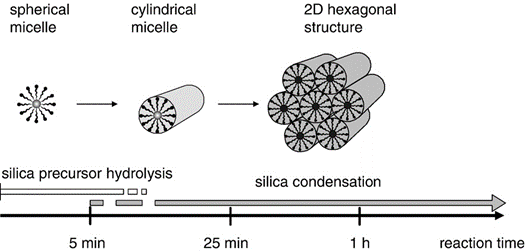

Initial micelle formation

In the acidic synthesis solution (pH ~1), the Pluronic P123 triblock copolymer (EO20PO70EO20) forms spherical micelles. The hydrophobic polypropylene oxide (PPO) blocks constitute the micelle core, while the hydrophilic polyethylene oxide (PEO) blocks form the corona [3,4].

TEOS hydrolysis and silica-micelle interaction

Upon addition of TEOS, hydrolysis occurs:

Si(OC2H5)4 + 4H2O → Si(OH)4 + 4C2H5OH

The hydrolyzed silica species interact with the PEO blocks in the micelle corona, increasing its electron density [5,6]. This interaction is driven by hydrogen bonding between the silanol groups and the ether oxygen atoms in the PEO chains.

Micelle elongation

Between 5-20 minutes after TEOS addition, the interaction with silica species causes the micelles to transform from spherical to cylindrical shape. Hybrid organic-inorganic cylindrical micelles form with gradually increasing aspect ratios [5,6,7]. This transformation is believed to be driven by the changing hydrophilic-lipophilic balance of the system as silica species associate with the PEO blocks.

Self-assembly and precipitation

Around 20-25 minutes into the synthesis, the cylindrical hybrid micelles begin to aggregate and pack together, leading to the formation and precipitation of the characteristic 2D hexagonal structure of SBA-15 [5,6,7]. This self-assembly process is governed by a combination of van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions.

Mesostructure formation and silica network condensation

The precipitated material shows Bragg diffraction peaks characteristic of the 2D hexagonal phase. Initially, the cylinders are weakly linked via their coronas. Over the next 1-24 hours, silica species in the spaces between cylinders undergo condensation reactions, resulting in cross-linking and covalent bonding between coronas of cylindrical micelles [5,6,8]:

(OH)3Si-O-Si(OH)3 + (OH)3Si-O-Si(OH)3 → (OH)3Si-O-Si(OH)2-O-Si(OH)2-O-Si(OH)3 + H2O

This condensation process is critical for the development of the rigid silica framework as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The three initial stages of the SBA-15 synthesis. [4]

Structural refinement and template removal

Further condensation reactions at elevated temperatures (80-100°C) lead to densification of the silica network, accompanied by a slight decrease in the unit cell parameter and an increase in pore size. Finally, calcination at 500-550°C removes the Pluronic template, leaving the porous SBA-15 structure [8,9,10]. During this process, micropores within the pore walls may form as a result of the removal of PEO chains that were embedded in the silica framework.

Optimization Strategies

Several key parameters can be optimized to achieve high surface area SBA-15 materials:

Temperature control

A two-step temperature process is typically employed:

- Initial self-assembly at 35-40°C for 20-24 hours

- Hydrothermal treatment at 80-100°C for 24-48 hours

Higher hydrothermal temperatures (up to 120°C) can increase pore size but may decrease surface area [1,10]. The initial low-temperature step is crucial for the formation of well-ordered cylindrical micelles, while the higher-temperature step promotes silica condensation and structural refinement.

pH

Strongly acidic conditions (pH ~1) using 1.6-2M HCl are optimal for SBA-15 synthesis [1,3,4]. The low pH serves several purposes:

- It slows down the hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS, allowing for better control over the process

- It promotes the formation of protonated silica species that interact more strongly with the PEO blocks

- It influences the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance of the Pluronic copolymer, favoring the formation of cylindrical micelles

Reagent ratios

An optimal molar composition is: 1 TEOS : 0.017 P123 : 5.7-6 HCl : 193-195 H2O [1,4]. This ratio ensures:

- Sufficient silica precursor for framework formation

- Appropriate surfactant concentration for micelle formation and ordering

- Adequate acidity for controlled silica condensation

Aging time

Extended aging times (up to 24-48 hours) at the hydrothermal temperature can increase surface area and improve ordering [1,3]. Longer aging times allow for:

- More complete silica condensation

- Better definition of the mesoporous structure

- Potential growth of micropores within the pore walls

Template removal

Calcination at 500-550°C for 5-6 hours is typically sufficient to fully remove the P123 template [1,9]. Alternative methods for template removal include:

- Solvent extraction: Can preserve more of the original structure but may be less complete

- Microwave-assisted extraction: Faster but requires specialized equipment

- Ozone treatment: Can be effective at lower temperatures but may introduce surface defects

Addition of inorganic salts

Adding small amounts of KCl or NaCl during synthesis can increase surface area and improve hydrothermal stability [11,12]. The salt effect is attributed to:

- Altering the micellization behavior of the Pluronic copolymer

- Influencing the silica condensation process

- Potentially stabilizing the mesoporous structure during template removal

Post-synthesis treatment

Avoiding washing with water or ethanol before calcination can prevent structural shrinkage. Direct calcination of the as-synthesized material preserves more micropores [3]. Post-synthesis modifications can also be employed to tailor the properties of SBA-15:

- Grafting of organic functional groups

- Introduction of heteroatoms (Al, Ti, Zr) for catalytic applications

- Pore expansion using swelling agents

Controlled rate of TEOS addition

Slow, dropwise addition of TEOS can improve ordering [4,8]. This approach allows for:

- More uniform distribution of silica species

- Better control over the micelle elongation process

- Improved homogeneity of the final material

Stirring conditions

Gentle stirring during initial assembly followed by static conditions during hydrothermal treatment is optimal [1,4]. This protocol ensures:

- Uniform distribution of reagents during the initial stages

- Undisturbed self-assembly and structural refinement during aging

Silica source

TEOS generally produces higher surface areas compared to tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS) or tetrapropyl orthosilicate (TPOS) [12]. The choice of silica precursor affects:

- Hydrolysis and condensation rates

- Interaction with the Pluronic copolymer

- Potential for generating micropores

Microporosity and wall thickness

Materials with more micropores tend to have higher surface areas and better hydrothermal stability. Thicker pore walls (3-6 nm) contribute to higher hydrothermal stability but may slightly reduce surface area [9,10]. Balancing these factors is crucial for optimizing SBA-15 properties.

Characterization Techniques

Proper characterization is essential for understanding and optimizing SBA-15 materials. Key techniques include:

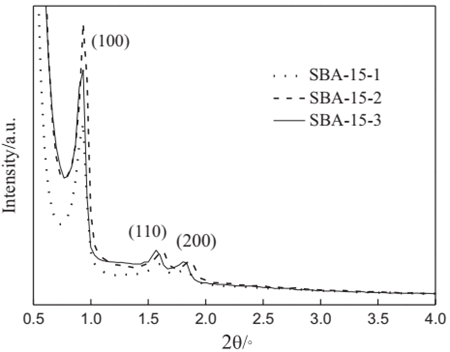

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

- Provides information on the long-range ordering and symmetry of the mesoporous structure

- Allows determination of the unit cell parameter

Figure 3 XRD patterns of SBA-15 synthesized by addition of different amounts of PVA powder and calcined for 6 h at 550 1C in air. [12]

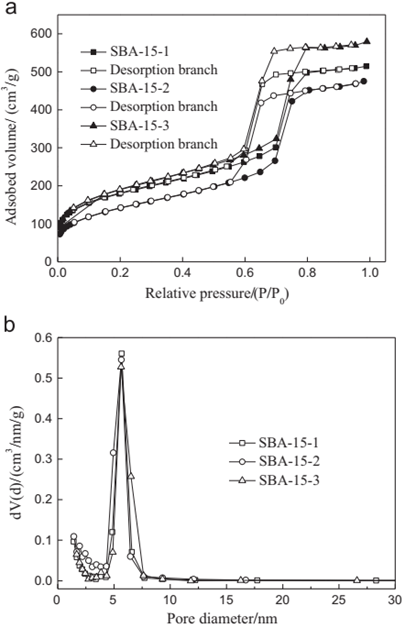

Nitrogen Adsorption-Desorption

- Yields data on surface area (BET method), pore volume, and pore size distribution

- Provides insights into the presence of micropores (t-plot method)

Figure 4 N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (a) and pore size distribution curves (b) of calcined SBA-15 samples. [12]

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- Offers direct visualization of the mesoporous structure and pore ordering

- Can reveal information about particle morphology and pore connectivity

Figure 5 TEM images of calcined hexagonal SBA- 15 mesoporous silica with different average pore sizes, from BET and XRD results (24): (A) 60 Å, (B) 89 Å, (C) 200 Å, and (D) 260 Å. The thicknesses of the silica walls are estimated to be (A) 53 Å, (B) 31 Å, (C) 40 Å, and (D) 40 Å. [1]

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS)

- Allows in situ monitoring of the formation process

- Provides detailed information on the mesoscale structure

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

- 29Si NMR can provide information on the degree of silica condensation

- 1H NMR can be used to study the behavior of the Pluronic template

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

- Useful for monitoring the removal of the organic template

- Can provide information on surface functional groups

Applications of SBA-15

The unique properties of SBA-15 make it suitable for a wide range of applications:

Catalysis

- Support for metal nanoparticles in heterogeneous catalysis

- Direct incorporation of catalytic sites (e.g., acid sites for petrochemical processes)

- Enzyme immobilization for biocatalysis

Adsorption and Separation

- Gas storage and separation

- Removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants from water

- Chromatographic applications

Drug Delivery

- Controlled release of pharmaceuticals

- Protection of sensitive drug molecules

- Targeted delivery through surface functionalization

Sensors and Devices

- Host for luminescent materials in optical sensors

- Component in electrochemical sensors

- Template for the synthesis of nanostructured materials

Energy Applications

- Support for electrocatalysts in fuel cells

- Host for energy storage materials (e.g., lithium-ion batteries)

- Component in solar cells and photocatalytic systems

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the significant progress in SBA-15 synthesis and applications, several challenges remain:

Scalability

- Developing methods for large-scale production while maintaining structural quality

- Addressing issues related to batch-to-batch reproducibility

Customization

- Fine-tuning pore size, wall thickness, and surface chemistry for specific applications

- Developing new synthesis strategies for hierarchical porous structures

Stability

- Further improving hydrothermal and mechanical stability for industrial applications

- Enhancing the stability of functionalized SBA-15 materials

Advanced applications

- Exploring the potential of SBA-15 in emerging fields such as quantum dot synthesis, thermoelectrics, and advanced membrane technologies

- Developing SBA-15-based composite materials with synergistic properties

Conclusion

By optimizing the synthesis parameters discussed in this review, surface areas over 850-1000 m²/g have been reported for SBA-15 [1,9,12]. The highest surface areas tend to be achieved with a balance between wall thickness, pore size, and microporosity. It’s important to note that there’s often a trade-off between maximizing surface area and maintaining good hydrothermal stability [9,12].

SBA-15 represents a significant advancement in the field of mesoporous materials, offering a versatile platform for a wide range of applications. The ability to fine-tune its structural and textural properties through careful control of synthesis conditions makes it a powerful tool in materials science and engineering.

Future research directions may include:

- Developing novel synthesis strategies to further increase surface area while maintaining structural integrity

- Exploring the use of different structure-directing agents to create new mesoporous architectures

- Investigating the impact of various additives on the textural properties of SBA-15 materials

- Combining SBA-15 with other functional materials to create advanced composites

- Expanding the application of SBA-15 in emerging technologies such as energy storage, environmental remediation, and nanomedicine

As our understanding of the formation mechanism and structure-property relationships of SBA-15 continues to grow, we can expect to see even more innovative applications and optimized synthesis strategies in the future.

References

- Zhao, D. et al. Science, 1998, 279, 548-552.

- Zhao, D. et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1998, 120, 6024-6036.

- Kruk, M. et al. Chem. Mater., 2000, 12, 1961-1968.

- Zholobenko, V.L. et al. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2008, 142, 67-74.

- Impéror-Clerc, M. et al. Chem. Commun., 2007, 834-836.

- Flodström, K. et al. Langmuir, 2004, 20, 4885-4891.

- Ruthstein, S. et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 3366-3374.

- Khodakov, A.Y. et al. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 22780-22790.

- Zhang, F. et al. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 8723-8732.

- Fulvio, P.F. and Jaroniec, M. J. Mater. Chem., 2005, 15, 5049-5053.

- Linton, P. et al. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2010, 12, 3852-3858.

- Wang, J. et al. Mater. Lett., 2015, 145, 312-315.

- Kresge, C.T. et al. Nature, 1992, 359, 710-712.