Chemical stability is a crucial concept in chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and materials science. It refers to the ability of a compound or mixture of compounds to maintain its integrity and resist undergoing unwanted chemical reactions or decomposition under specified conditions. This article explores the fundamental principles of chemical stability and the methods used to assess it.

Fundamentals of Chemical Stability

The stability of a chemical compound is influenced by various factors, including:

- Molecular structure

- Intermolecular forces

- Environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, pH, light exposure)

- Presence of catalysts or inhibitors

Understanding these factors is essential for predicting and controlling the stability of chemical formulations in different applications.

Measuring Chemical Stability

Assessing chemical stability often involves accelerating potential chemical reactions that occur slowly under normal conditions. The primary method for achieving this acceleration is through controlled heating.

The Arrhenius Equation

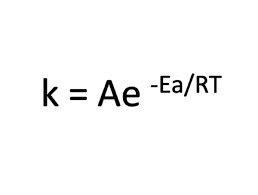

The relationship between temperature and reaction rate is described by the Arrhenius equation:

Where:

- k is the rate constant

- A is the pre-exponential factor (a constant)

- Ea is the activation energy

- R is the universal gas constant

- T is the absolute temperature

This equation demonstrates that as temperature increases, the reaction rate increases exponentially. As a general rule of thumb, a temperature increase of 10°C approximately doubles the rate of reaction.

Challenges in Stability Testing

While the principle of accelerated testing through increased temperature seems straightforward, it presents several challenges:

- Activation Energy Threshold: Elevated temperatures may provide sufficient energy to overcome activation barriers for reactions that would not occur under normal conditions. This can lead to the initiation of unintended reactions.

- Complex Formulations: Many products, especially in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, contain multiple compounds. At higher temperatures, it becomes difficult to distinguish between the accelerated reactions of interest and parasitic reactions that only occur at elevated temperatures.

- Extrapolation Limitations: Data obtained at high temperatures may not always accurately predict long-term stability at lower temperatures due to potential changes in reaction mechanisms.

Optimizing Stability Testing Strategies

To address these challenges, a multi-temperature approach is often employed:

- Low-Temperature Condition: Samples are stored at room temperature +10°C to +15°C. This condition provides the most accurate and representative results but requires the longest testing period.

- High-Temperature Condition: Samples are subjected to temperatures around 80°C to 90°C. This condition yields the fastest results but is least accurate due to potential parasitic reactions.

- Intermediate Temperature Condition: Samples are stored at a temperature midway between the low and high conditions. This helps reduce noise from high-temperature parasitic reactions while providing preliminary results in a reasonable timeframe.

By comparing data from these different conditions, scientists can make more informed predictions about long-term stability while balancing the need for timely results.

Additional Considerations

- Humidity Control: In addition to temperature, controlling humidity during stability testing is crucial, especially for moisture-sensitive compounds.

- Photostability: For light-sensitive materials, photostability studies should be conducted alongside thermal stability tests.

- Packaging Interactions: The interaction between the chemical formulation and its packaging can significantly impact long-term stability.

- Analytical Methods: Employing sensitive and specific analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, mass spectrometry) is essential for accurately quantifying degradation products and minor changes in chemical composition.

- Kinetic Modeling: Advanced kinetic modeling techniques can help extrapolate high-temperature data to predict long-term stability at lower temperatures more accurately.

Stability Considerations for Different Formulation Types

When assessing chemical stability, it’s crucial to consider the base of the formulation, as different bases exhibit varying levels of thermal stability. This section explores the stability characteristics of oleaginous and aqueous formulations, as well as the implications for testing methodologies.

Oleaginous Formulations

Oleaginous formulations, which are based on oils or fats, generally demonstrate higher thermal stability compared to aqueous systems. These formulations can often withstand higher temperatures without significant degradation of their chemical components, offering several advantages in stability testing. However, it’s crucial to note that the maximum testing temperature for oleaginous bases is constrained by an important factor: the cloud point of the formulation components.

Cloud Point Considerations

The cloud point is the temperature at which dissolved solids are no longer completely soluble, precipitating as a second phase and turning the liquid cloudy. For oleaginous formulations:

- Maximum Temperature Limitation: The highest testing temperature should remain below the lowest cloud point of any component in the formulation. This precaution ensures that the formulation remains in a single phase throughout the testing process.

- Safety Margin: To be safe, it’s recommended to set the maximum testing temperature sufficiently below the lowest cloud point. This margin accounts for potential variations in the formulation and ensures consistent test conditions.

- Component Analysis: Before designing a stability testing protocol, it’s essential to know the cloud points of all major components in the oleaginous formulation.

- Impact on Testing Strategy: While oleaginous formulations can theoretically withstand temperatures up to 120°C, the actual maximum temperature used in stability testing may be lower, depending on the specific components of the formulation.

Given these considerations, the advantages of testing oleaginous formulations at higher temperatures include:

- Extended Temperature Range: Even with cloud point limitations, oleaginous formulations typically allow for testing at higher temperatures compared to aqueous systems, enabling more aggressive acceleration of potential degradation reactions.

- Reduced Testing Time: Higher testing temperatures can potentially shorten the overall duration of stability studies for oleaginous products, although this must be balanced against the risk of inducing unrepresentative degradation pathways.

- Broader Applicability: Products intended for high-temperature applications can be more accurately assessed under conditions closer to their intended use.

However, it’s important to note that even within oleaginous formulations, individual components may have different temperature sensitivities, and careful monitoring of all constituents is necessary.

Aqueous Formulations

In contrast to oleaginous systems, aqueous formulations face significant limitations in high-temperature stability testing:

- Water Loss: Aqueous bases typically cannot be tested above 80°C without risking significant water loss from the formulation. This loss can dramatically alter the concentration of other components, potentially leading to misleading stability data.

- Hydrolysis Acceleration: Higher temperatures can disproportionately accelerate hydrolysis reactions, which may not accurately reflect the product’s stability under normal conditions.

- Phase Changes: As temperatures approach the boiling point of water, the risk of phase changes increases, which can fundamentally alter the formulation’s characteristics.

Emulsions and Colloidal Systems

It’s worth noting that emulsions and other colloidal systems are likely to break or undergo phase separation at elevated temperatures. However, in the context of chemical stability testing, these physical changes are generally considered separately from chemical degradation:

- Focus on Chemical Stability: The primary goal of these tests is to assess the chemical stability of the individual components, rather than the physicochemical stability of the system as a whole.

- Separating Chemical and Physical Changes: While the breaking of an emulsion at high temperatures is an important observation, it should be evaluated separately from the chemical stability data. This physical change doesn’t necessarily indicate chemical instability of the components.

- Analytical Considerations: When testing these systems, it may be necessary to separate phases before analysis to accurately quantify any chemical changes in individual components.

Implications for Stability Testing Strategies

The differences in thermal stability between oleaginous and aqueous formulations have important implications for designing stability testing protocols:

- Customized Temperature Ranges: Testing temperatures should be tailored to the formulation type. While an oleaginous product might be tested at 120°C, 80°C, and room temperature +15°C, an aqueous product might require a lower high-temperature point, such as 70°C, 50°C, and room temperature +10°C.

- Analytical Method Adaptation: Methods for analyzing chemical changes in oleaginous systems at high temperatures may need to be distinct from those used for aqueous systems.

- Interpretation of Results: When extrapolating high-temperature data to predict room temperature stability, the base formulation type must be taken into account. Extrapolations for aqueous systems tested at lower maximum temperatures may require longer overall testing periods to achieve comparable predictive power.

- Component-Specific Considerations: Even within a primarily oleaginous or aqueous system, individual components may have different stability profiles. It’s crucial to monitor all key ingredients, not just the overall formulation.

By recognizing and accounting for these differences in formulation bases, researchers can design more effective and relevant stability testing protocols, leading to more accurate predictions of long-term product stability across various formulation types.

Conclusion

Chemical stability testing is a complex but essential process in ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of chemical products. By understanding the principles of chemical kinetics and employing strategic testing methods, scientists can make informed decisions about formulation stability and shelf life. As analytical techniques and modeling capabilities continue to advance, our ability to predict and control chemical stability will undoubtedly improve, leading to safer and more effective products across various industries.